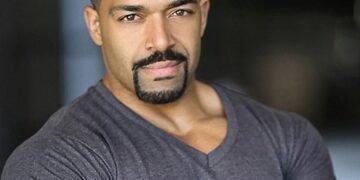

In the heart of Stanford University, where satellites are imagined and climate futures are charted, one lab hums with a different kind of purpose. It’s not just about equations or efficiency. It’s about equity. And at its helm is a man whose life began not in privilege or proximity to power, but in the dust and determination of a Kenyan refugee camp.

Dr. Khalid Osman doesn’t just build water systems. He rebuilds the very idea of who gets to belong in the future we engineer.

“You can’t retrofit justice,” Osman says. “You have to embed it at the blueprint stage.”

The Boy Who Remembered Thirst

Khalid Osman was born in Mombasa—not the coastal Kenya of postcards, but the forgotten Kenya of temporary tents, rationed water, and restless dreams. His Somali family had fled civil war and landed in a refugee camp where running water wasn’t a given and electricity was borrowed from wires that buzzed like warnings.

Even as a toddler, Khalid’s earliest memories were sensory: the sting of thirst, the metallic taste of storage tank water, the sounds of adults negotiating dignity in a place designed for survival, not hope.

At just two years old, his family was granted asylum in the United States. They settled in Portland, Oregon, where paved streets and flashing crosswalks introduced a new kind of bewilderment. But Khalid noticed something most kids didn’t: some neighborhoods had smoother roads, brighter lights, cleaner water—and others didn’t.

“It wasn’t just poverty,” he would later say. “It was designed inequality.”

Then came 9/11. As a Muslim child in America, Khalid’s accent was met with suspicion. His name drew whispers. His classmates, not understanding the geography of grief, called him a terrorist. For years, he didn’t have the language to describe what was happening. But he had something better: math.

Math, he discovered, didn’t stereotype. It didn’t mock. It had no bias. And through it, Khalid found power—not just to solve problems, but to reimagine systems.

From Numbers to Justice: The Ascent of an Engineer

By middle school, he had already decided: he would become an engineer. But not the kind who simply calculated pressure loads or water flow rates. Khalid wanted to rebuild the very bones of the city—its pipelines, grids, and structures—with justice as his blueprint.

That path wasn’t easy. It took grit, scholarships, and mentors who saw his potential. But step by step, he climbed:

- University of Portland, where he blended engineering with ethics.

- UT Austin, where he earned his MS and PhD on full fellowships from the Gates Millennium Scholars Program and the Ford Foundation.

- And finally, Stanford, where he now leads his own lab.

But make no mistake—Khalid Osman didn’t arrive at Stanford to assimilate.

He came to transform.

The Osman Lab: Where Equity is a Starting Point, Not an Afterthought

Founded in 2022, The Osman Lab is unlike anything Stanford has seen. Where traditional engineering asks, “How can we build this cheaper or faster?” Osman’s team asks, “Who has been excluded? Who bears the cost? Who gets left behind?”

It’s engineering for those who’ve been ignored by design..

In East Palo Alto, a working-class city overshadowed by its Silicon Valley neighbors, Osman’s team is developing metrics to measure water equity. Not just access, but affordability, reliability, and dignity.

In rural Kenya, they’re co-creating wastewater systems that don’t rely on massive pipes and city infrastructure—but that work, because they’re built with local wisdom.

“You can’t retrofit justice,” Osman says. “You have to embed it at the blueprint stage.”

They’re even building AI models that predict flooding in informal settlements, and algorithms that prioritize resource distribution for the most vulnerable—not the wealthiest.

In a world hurtling toward climate crisis, Khalid’s lab is a lifeline for the communities that climate policy often forgets.

Returning to Kenya with Purpose, Not Pity

Khalid’s relationship with Kenya isn’t nostalgic—it’s strategic, sacred, and deeply active.

He doesn’t visit as an outsider offering solutions. He returns as a son of the soil, asking questions, listening, learning. His fieldwork in Nairobi’s informal settlements and Mombasa’s coastal communities is about partnership, not intervention.

“Kenya doesn’t need saviors,” he insists. “It needs systems that listen.”

His lab actively mentors African scholars—engineers like Dr. Aggrey Muhebwa from Uganda and Oluchukwu Obinegbo from Nigeria—ensuring the next generation doesn’t have to choose between global excellence and local impact.

And through his co-leadership of the Building Africa’s Cities Summit, Khalid is working to shift billions in infrastructure funding toward models that center community voices.

Engineering Belonging: The True Infrastructure Project

For Khalid, engineering is never just technical. It’s spiritual. It’s personal. It’s political.

In the classrooms of Stanford, he is often the only Black Muslim civil engineer. So he recruits differently. He builds bridges between HBCUs, community colleges, and Kenyan universities, creating onramps for students who, like him, were never supposed to be in the ivory tower.

Inside his lab, young researchers like Sinna Nick from East Palo Alto say working with Osman isn’t just career-shaping—it’s life-affirming.

“We’re not just building water models,” Sinna says. “We’re building a world where we belong.”

Conclusion: The Map Home

Khalid Osman’s life began in a camp that taught him that infrastructure, when broken, isn’t abstract—it’s lethal. That lesson never left him. It echoes in every algorithm his team writes, every system they design, every community they stand beside.

His greatest innovation isn’t a pipeline or sensor.

It’s a redefinition of what it means to belong in the world we build.

Because Khalid knows: the true architecture of the future is not concrete. It’s inclusion. It’s dignity. It’s justice.

And in that future, a child born in a refugee camp walks into a Stanford lecture hall—not as a symbol of luck, but as proof of what happens when we finally design systems that remember everyone.