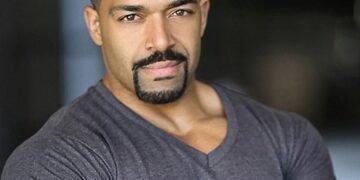

On a chilly London evening, under the pulsing lights of a cramped comedy basement in Soho, a young woman steps onto the stage in sneakers and self-assurance. The mic crackles. She flashes a knowing smile. And then—within seconds—she has the room. Sharon Wanjohi doesn’t just tell jokes. She conducts cultural symphonies. Her punchlines swing between Kikuyu aunties and British awkwardness, between childhood prayers and queer awakenings, between her uncle’s pub and the absurdity of British politeness. The audience laughs because they see themselves. Or they laugh because they don’t—but want to understand.

That’s her magic. That’s Sharon.

From Horsham with a Hint of Nairobi

To know Sharon Wanjohi is to know what it means to grow up between worlds. Born in Kenya but raised in Horsham, West Sussex, her story isn’t about choosing sides. It’s about wielding both. Her childhood was layered—prayers in Kikuyu whispered at night, laughter-filled summer visits to relatives in Nairobi, all set against the backdrop of British suburbia where no one could quite pronounce her name. That blend—the Kenyan warmth and British wit—formed the crucible of her comedy.

For many, this dual identity might have been a burden. For Sharon, it became a resource. It taught her the subtle differences in how humour works: the cheeky storytelling of Kenyan homes where everyone’s a character in a saga, and the dry, self-effacing banter of British schools. She didn’t just learn to switch languages; she learned to switch comedic registers.

Funny Women, Real Struggles, Big Stages

In 2021, her talent broke through the noise. Sharon became a finalist in both the Funny Women Stage Awards and the Chortle Student Comedy Awards—no small feat in a field still slow to recognize Black, queer, and immigrant voices. But Sharon wasn’t interested in assimilation. Her comedy wasn’t diluted—it was sharpened by her truth. Whether unpacking mental health taboos in African households or lampooning British people’s obsession with queuing, she refused to play it safe.

Her appearance on Channel 4’s Jokes Only a Lesbian Can Tell was an early masterstroke. Her routine wasn’t just funny—it was bold, disarming, and unexpectedly tender. She peeled back the layers of identity politics with charm and precision, affirming that the more specific her story, the more universal the laughter.

“My mum once told me to ‘stop crying or I’ll give you something to cry about,’” she recounts. “I said, ‘But I’m already crying?’” That moment—where pain meets hilarity—is where Sharon shines brightest.

The Fringe: Where Kenya Met the Mic

But the true test came at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe—the brutal proving ground of comedy careers. Sharon’s 2023 debut, Screaming, Crying, Throwing Up (with Abbie Edwards), was raw,

honest, and packed. The following year, she returned solo with In the House, a riotous parody of self-help culture framed around a fictional “worst-selling” book hawked from her uncle’s pub. That pub wasn’t just a prop—it was a metaphor. For family. For inherited wisdom. For the complicated love in diaspora households. The show was absurdist and hilarious, but rooted in lived experience—Kenyan, queer, diasporic, proud.

A Voice Behind the Scenes—and Center Stage

Offstage, Sharon’s fingerprints are everywhere. She’s written for Never Mind the Buzzcocks, The Jonathan Ross Show, Late Night Lycett, and more. Her wit, honed by years of cross-cultural navigation, has found a home in British mainstream media—not by softening her voice, but by making it louder, sharper, and unmistakably hers.

She’s appeared on ITV’s The Stand Up Sketch Show, BBC Three’s New Comedy Awards, and Comedy Central Live. Each time, she brought a version of Kenya with her—sometimes in the form of a Kikuyu grandmother, other times as a punchline about African parenting, always infused with her signature comedic honesty.

Her 2025 Chortle Best Newcomer nomination wasn’t just recognition. It was a declaration: Sharon Wanjohi is no longer emerging. She’s here.

Kenya, Always in the Room

Even when she doesn’t mention it, Kenya is always in her act.

You can hear it in her pacing—storytelling that dances rather than marches. You can hear it in the rhythm of her callbacks, the warmth in her mimicry of mothers and aunties, the unfiltered wisdom of a child raised by a culture that doesn’t believe in sugar-coating truth. She doesn’t explain Kenya to her audience—she invites them in.

In one routine, she jokes about how British people apologize when someone else bumps into them. “You’d never catch a Kenyan doing that,” she grins. “We’d be like ‘Angalia! You don’t have eyes?’” The audience erupts—not just in laughter, but in recognition. Because Sharon’s comedy doesn’t only punch up. It pulls you in.

And when she talks about mental health in African families, she doesn’t mock. She reveals. The silence. The stigma. The love buried beneath discipline. “My mum once told me to ‘stop crying or I’ll give you something to cry about,’” she recounts. “I said, ‘But I’m already crying?’” That moment—where pain meets hilarity—is where Sharon shines brightest.

Representation Without Apology

What Sharon represents goes beyond comedy. She’s the image of a Kenyan diaspora that refuses to be flattened. Queer, Black, female, immigrant—each label comes with assumptions. Sharon turns those assumptions into punchlines, then turns the punchlines into bridges.

She’s not a spokesperson. She’s not a stereotype. She’s just brilliantly, stubbornly, unapologetically herself. And in being so, she gives others—especially young diasporans—the permission to do the same.

The Last Laugh? Just the Beginning.

There’s a quiet revolution happening in comedy, and Sharon Wanjohi is leading it—one joke, one awkward silence, one explosive laugh at a time. With her Kenyan heart, British training, and global vision, she’s forging a path that’s both wildly entertaining and deeply necessary.

As she says at the close of one set: “My mum wanted me to be a lawyer. And I guess I am… because every night, I get up here and make my case for being exactly who I am.”

And the jury? They’re laughing—and standing on their feet.