For many, Barack Obama’s rise to the presidency of the United States is the archetypal American success story — the son of a single mother, raised with modest means, propelled by education and grit, and elevated by hope to the highest office in the land. But beneath that well-known arc lies another story. One less told, but no less foundational: the story of Kenya — the land that called him home, helped him reconcile his identity, and ultimately forged the man who could shoulder the weight of global leadership.

It is a story of return. Of longing. Of healing. And of what happens when a soul scattered across continents finds its way back to the soil it never stopped belonging to.

The Myth and the Absence

Long before he ever set foot on Kenyan soil, Barack Obama carried it within him — not through memory, but through myth.

As a child growing up in Hawaii and later Indonesia, “Barry” Obama knew his father only through stories. Barack Obama Sr. was a distant, almost mythic figure — a brilliant scholar from Kenya who had crossed oceans to study in America. To young Barack, his father wasn’t a reminder of abandonment, but a symbol of possibility. In his imagination, Kenya wasn’t an unfamiliar land; it was a place of dignity, intellect, and promise. “He had gone to learn the white man’s magic and return to Kenya to develop the country,” Obama once said, echoing the myth he grew up believing.

Yet this imagined connection masked a deeper ache — a hunger for grounding. For identity. For answers.

The Dislocation of Duality

Obama often spoke of his duality — being Black in America but not fully African American, his lineage not tied to the legacy of slavery but to an African father he barely knew. This left him suspended between worlds. When he finally met his father briefly at age ten, it only deepened the distance. The man was charming but unfamiliar — a visitor with a deep voice and a British accent, more silhouette than substance.

So the questions lingered. Who was his father really? Who were his people? And where, in this sprawling narrative, did he truly belong?

“Feeling accepted by them was important for me,” Obama said later. “It sort of filled the hole that I had felt for a long time.” – Referring to Kenya & his Kenyan Family during his first trip to Kenya in 1988 at 27 years of age

The Journey Back: Kenya, 1988

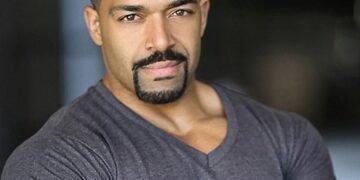

In 1988, at the age of 27, Barack Obama boarded a plane to Kenya. Armed with a Columbia degree and a growing commitment to public service, he arrived not as a tourist, but as a pilgrim in search of home.

Waiting to receive him was his half-sister, Dr. Auma Obama, who captured the visit in an intimate documentary. “We have a visitor from America… my brother!” she beamed. But underneath the warmth lay quiet uncertainty. “I was afraid that Barack would not be comfortable with us,” Auma admitted. “That we wouldn’t know how to relate to him — after all, he was from a totally different world.”

The cultural and emotional terrain proved just as unfamiliar. Obama was welcomed with affection, yet marked as an outsider. He couldn’t speak Dholuo. He didn’t understand the traditions. At times, he felt like a “white among blacks.” Even simple questions — about family disputes or burial rites — yielded vague or contradictory answers. “Nobody really knows why,” one relative said of an old custom. The traditions were there, but fraying. The clarity he sought was buried beneath layers of memory, silence, and change.

And yet, this was the gift. Kenya wasn’t offering him perfection. It was offering him truth — messy, alive, and profoundly human.

Touching the Soil, Meeting the Blood

The most profound moments came in the village of Kogelo in Siaya County — his father’s ancestral home. There, Barack met his grandmother, Sarah Hussein Obama, known simply as Mama Sarah. A formidable woman of few words, she embraced him not with fanfare but with the quiet acceptance of kin.

He visited his father’s grave. And those of other forebears. He stood in the place where stories had begun, stories that were once distant and abstract, but now pulsed with blood and breath. In that act — of standing where generations of Obamas had lived, struggled, and died — he felt something shift.

“Feeling accepted by them was important for me,” Obama said later. “It sort of filled the hole that I had felt for a long time.”

A Political Education Beyond the West

Beyond family, Obama encountered a Kenya in transition — full of contradiction and clarity alike.

He met university students who had been expelled for protesting fee increases. He listened to stories of injustice, economic frustration, and political repression. He observed the lingering effects of colonialism in subtle acts — the white expatriates still receiving deference in restaurants, the absence of local empowerment. “The engine for growth… may not be there,” he noted, warning that unmet expectations among Kenya’s youth was a recipe for unrest. “You’d think that would be more of a source of concern for the government.”

These weren’t just observations. They were insights. Seeds. Lessons that would bloom later into policies, into worldview, into the calm conviction he would carry into the Oval Office.

Becoming Ja Kogelo

In Kenya, Obama wasn’t trying to become someone new. He was becoming whole.

The experience gave birth to Dreams from My Father, a memoir that reads like a reckoning — with identity, history, and the ghosts of absence. It was a Kenyan-American story, written in American prose but rooted in African soil. In writing it, he claimed his dual inheritance. He became Ja Kogelo — son of Kogelo — not through blood alone, but through belonging.

This belonging was his superpower. Not in politics, but in personhood. Kenya gave him what no election could: an internal compass. An unshakeable self.

Kenya’s Quiet Imprint on a President

The lessons of Kenya traveled with him all the way to the White House:

- Complexity without Fear: Navigating Luo customs, strained family ties, and political contradictions gave him the ability to hold multiple truths — a skill that would become central to his leadership.

- Empathy Beyond Borders: Unlike most American presidents, Obama had lived — even briefly — in the Global South. He understood development and dignity not as policy points, but as personal realities.

- Unshakable Calm: “No Drama Obama” wasn’t a brand. It was the calm of a man who had faced the storm of dislocation — and come through whole.

- Mastery of Narrative: By reconciling his own story, Obama learned how to connect stories — the personal and the political, the individual and the collective.

- Authenticity as Power: Barack Hussein Obama — a name once thought to be a liability — became a symbol of global possibility. He wasn’t trying to perform identity. He was identity.

A Message for the Diaspora

Kenya did not make Obama American. But it helped make him ready — for America, for the world, for history.

In his own words: “If you could build a strong Black country in Kenya… it sends a message to Black Americans. It sends a message that we can build.”

He saw Kenya’s potential not as nostalgia, but as future. Not just for himself — but for a generation scattered across continents, longing to root, to return, to build.

Obama’s story is not just a personal journey. It is the gold standard of the Kenyan Diaspora Dream — a dream where belonging heals identity, and identity fuels impact. His return home was not an ending. It was the moment the arc bent toward greatness.

He didn’t just become President. He became whole. And from that wholeness, he changed the world.